Harinder’s husband, the author Martin Jacques, remembers a most extraordinary person

Harinder Kaur Veriah was born in Assunta Hospital, close by Assunta Primary School, on December 31st, 1966. She came from a Punjabi family. From the beginning she faced great adversity. Her father, Karam Singh, a leading lawyer, who was also Malaysia’s youngest MP, was held for four years in solitary confinement under the Internal Security Act for leading a march of rubber plantation workers, who were demanding better conditions. Her mother, Harbens Kaur, a primary school teacher, died when Hari, as she was later known, was just six. Karam was a mercurial and inspirational figure but a largely absentee father. Hari, her older brother Kesh and sister Jessie were frequently left to fend for themselves. Money was of little consequence to Karam, he was motivated by a desire for political change: as a result the former was always very scarce. The children came from a materially poor but culturally rich background.

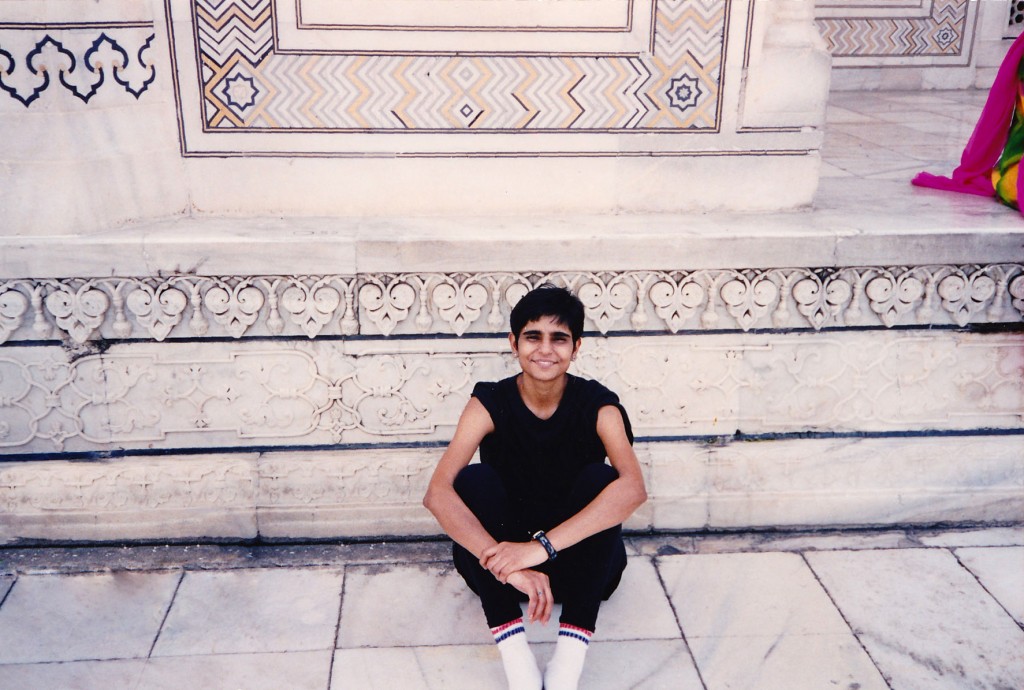

At the age of six, Hari went to Assunta Primary School and then at 12 to Assunta Secondary School, both all-girls schools. When Hari was in her mid-teens, she and her siblings went to live with two of her aunts and uncles after Karam remarried. Her last two years of her schooling were spent in Kota Bharu, the capital of Kelantan state, in the far north east of Malaysia, whose population was overwhelmingly Malay. Hari was often the only non-Malay girl in her class, an experience she came to greatly value. Hari was a proud Malaysian who counted Malays and Chinese as well as Indians as close friends.

Although several of her friends at Assunta Secondary School later went to the UK for their higher education, this was not an option for Hari. There was no one to provide for her: whatever money she had she had to earn. When it came to a career, given that her father was a lawyer and likewise two of her uncles, law was the obvious choice. She scrapped a living together by doing bits of teaching while in her spare time studying for a London University external degree in law. Once qualified, she began to practise in Kuala Lumpur as a commercial lawyer.

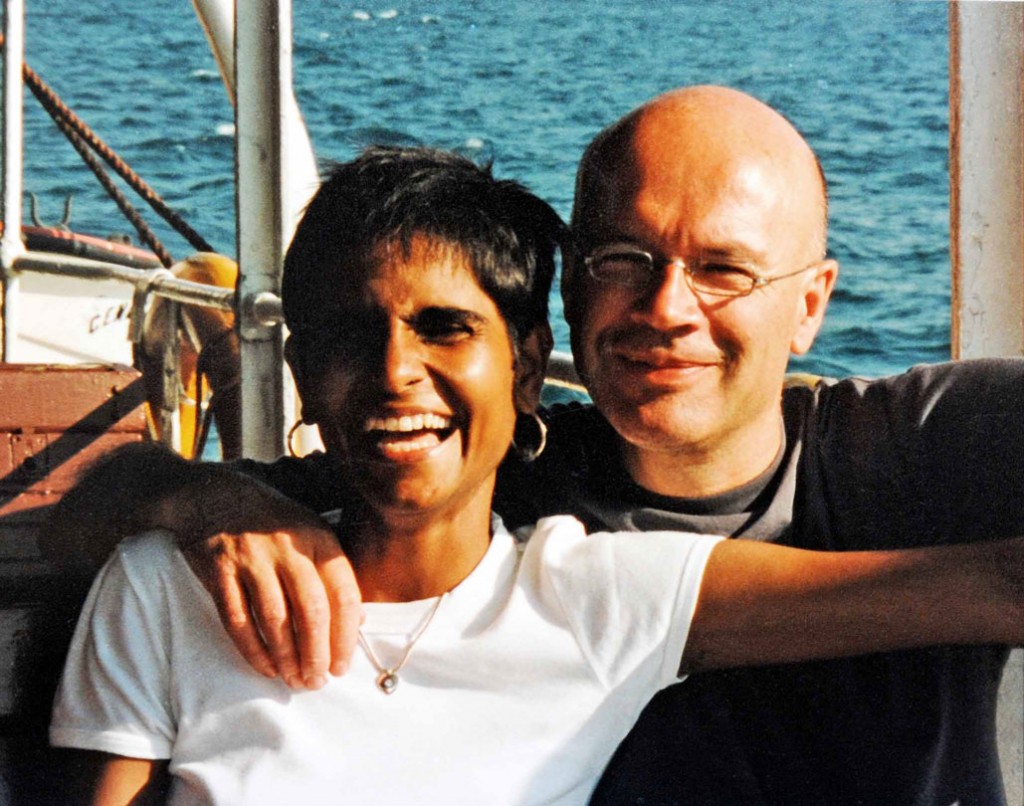

I met Hari a couple of years later, on August 21 1993. I was spending a few days holidaying on Tioman island, off the east coast of Malaysia. I went for an early morning run and as I was returning I noticed, at some distance, this figure walking between a couple of chalets. She stuck in my mind: I can’t tell you why. An hour or so later, I joined a group congregating for a jungle trek. Suddenly a voice behind me said: ‘Didn’t I see you earlier? Weren’t you running through the village?’ I turned round and before I could muster a word, she said with an impish grin, ‘Only a white man would do something as stupid as that.’ Then, reeling in the face of her audacity and wit, ‘she added, ‘Why did you come to Tioman?’ ‘A friend recommended it’, I replied weakly. ‘There are much more beautiful islands than this,’ she replied.

In a few short sentences Hari turned my life upside down. The jungle trek started to move off. I fell into animated conversation with her. Who was this woman I had just met and yet with whom I instantly felt enormous intimacy? She was from the other side of the world, from a former colony, now a developing country, from equatorial parts, her skin a beautiful dark brown: I was a pinky white colour, from a cold and wet island 6500 miles away to the north west. She was 26, I was 47. What did we have in common? Everything. In that moment, I knew I had met my soulmate. I fell in love with her in just a few short minutes.

Read A season in paradise by Martin Jacques

(Guardian, Saturday 30 November 2002)

Hari was a life force. She was possessed of great energy and vitality, a magnetism that drew people towards her, a humanity that made people instantly at home with her, a face that danced with emotion and warmth, a beautiful smile that lit up the world, an infectious humour that was irresistible, a kindness that was etched into her being, a wisdom that I had never known before. She already knew so much about life even though she was only in her mid-twenties. In that instant, I entered Hari’s gravitational field, never to leave it, even now, as I write, fifteen years after her death. The jungle trek was our beginning. The best thing I have ever done was to trust my emotions and feelings in that moment – and to move heaven and earth to make our relationship work. We both did.

A year later Hari moved to London. She did a masters in law. And then, after much angst and difficulty, she got a job as a lawyer in what is now Hogan Lovells, one of the City’s top law firms. It had not been easy. She was dark brown, from a developing country, not a product of privilege, and she had a 2:2 from her London University external degree (which, given her circumstances, was a formidable achievement). She was up against an army of privately educated candidates with firsts and upper seconds from Oxbridge, all with white faces. But once Hari finally managed to get an interview – which had begun to seem impossible – she got the job. As I always thought she would. She was irresistible, possessed of magic.

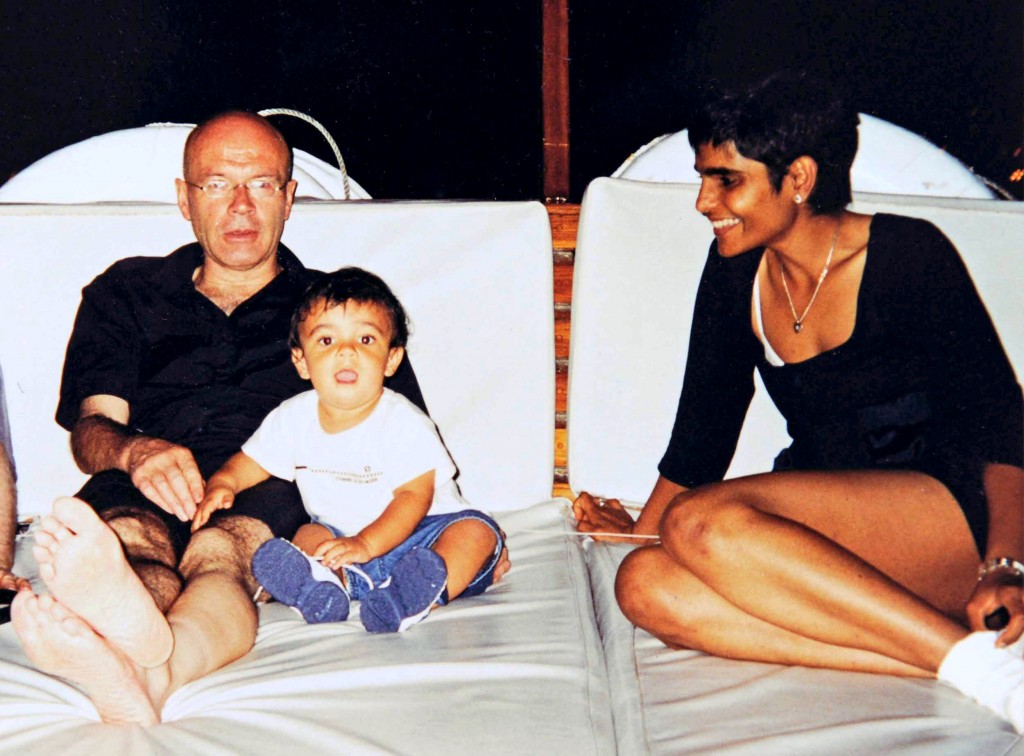

After two years working in the London office, the firm suggested that, in order to advance her career, she should consider a three-year secondment to the Hong Kong office. She thought it was probably a good idea. And it suited me: I was about to start work on my book, ‘When China Rules the World’. By now, Hari was pregnant. In November 1998, when we left for Hong Kong, Ravi, our son, was nine weeks old.

We enjoyed our time in Hong Kong but it was marred by the endemic racism that Hari was to suffer. Before we left, Hong Kong seemed like going to Hari’s part of the world: she spoke fluent Cantonese and some Mandarin, it was her time-zone, just over three hours flying time from Kuala Lumpur. Moreover, she had the kind of job that Hong Kong respected. In contrast, I was a self-employed writer, which enjoyed a rather lowly ranking in the Hong Kong pecking order. But soon we found that colour trumped all: Hari was bottom of the pile, I was at the top. She suffered racism in the street, from taxi drivers, in restaurants and, not least, in her workplace. Hari was not one to complain. She was never in denial, the opposite of naïve, she was, on the contrary, worldly wise about such matters. But she always sought to rise above such behaviour, to try and help those of such a mindset to overcome their prejudice.

But what if you are in hospital…

On the night of the millennium, we were out celebrating with friends when Hari had an epileptic fit, only the second of her life. She was taken to the Ruttonjee Hospital and kept in overnight and the following day. That evening I complained to her about the attitude of the doctor that was responsible for her care. Her reply was deeply disturbing. ‘I am bottom of the pile here.’ What do you mean, Hari, I asked, expecting her to tell me what had been going on. With resignation in a manner most untypical of Hari she said: ‘I am Indian and everyone else here is Chinese’. Hari could feel the prejudice. And she could hear it. She understood Cantonese. The staff assumed she couldn’t. I needed to get her out of that hospital. But it was late in the evening. I told the nurse on duty that I would be discharging Hari the following morning.

When I was getting ready to leave in the morning, I got a call from the hospital. Hari had had another epileptic fit. I should come to the hospital immediately. I arrived at her bedside just eleven minutes later to be confronted with an appalling scene. Hari was unconscious, the nurses clearly out of their depth, no doctor in sight. Hari died shortly afterwards, a victim of abject negligence resulting from racism.

She was just 33.

Her death became a major issue in Hong Kong. It led to a campaign for anti-racist legislation which was finally rewarded with success in July 2008. I fought a long court case against the Hospital Authority. For ten years they denied any responsibility. At the end of March 2010, just as the case was about to go to trial in the High Court, they raised the white flag and rushed to settle.

Read It seemed impossible, but at last Martin Jacques got justice for the wife he loved by Martin Jacques

(Observer, Sunday 4 April 2010)

Hari was the most extraordinary person I have ever met. She was highly intelligent, destined to go far and, if she had so wished, reach the top of her chosen field. But it was not this that marked her out as so special and so different. It was her humanity, her compassion, her kindness, her empathy for others, her wisdom, and her outlook on life.

She would have been delighted with our Assunta programme. Hari came from great hardship. Some people cannot relate to poverty because they have never known it. Others have known poverty but react to that experience by wanting to distance themselves as much as possible from the poor. In contrast, Hari’s experience of poverty ennobled her. She related with ease to those less fortunate than herself, felt an affinity with them, a need to befriend them, a desire to help them.

On Hong Kong Island there was a pedestrian underpass along which people with severe disabilities and without any means would congregate and solicit financial support from passing strangers. One Friday evening I met up with her after work. She asked if I had any change and I gave her what I had. As we walked along the underpass, she would give Ravi, who was then a little over a year old, some money, and he would walk up to one of the people and give it to them. She didn’t miss a single person. The look of surprise and delight on their faces was something to behold. It was one of the most heart-warming sights I have ever seen. It was so Hari, forever seeking to reach out to others. What a wonderful attitude to pass on to a toddler.

Further Reading

-

Eulogy

by Stuart Hall

-

Obituary

Guardian

-

Obituary

Independent

-

Negligence probe on epilepsy death

12/11/00 – The Sunday Times

-

Inquest hears of solicitor’s despair at being left ‘at the bottom of the pile’ before her death

14/11/00 – South China Morning Post

-

Racism row haunts probe into Hong Kong tragedy

-

Hong Kong reluctant to face up to racial discrimination: Minority communities and even mainland Chinese suffer pointed rudeness and prejudice in the territory

21/11/00 – The Financial Times

-

Hospital denies racism claims

22/11/00 – South China Morning Post

-

Lights turned off in a house lit by love

22/11/00 – South China Morning Post

-

Far from Equality

22/11/00 – South China Morning Post

-

More could have been done for lawyer

22/11/00 – South China Morning Post

-

Martin Jacques found his soul mate in Harinder Veriah

26/11/00 – South China Morning Post

-

Why have I been robbed of my wife?

26/11/00 – The Sunday Times

-

Authorities blind to the problem of racial discrimination

04/12/00 – South China Morning Post

-

SAR’s long, hard race row

29/12/00 – South China Morning Post

-

Hong Kong’s Big Dirty Little Secret

-

Racism In Hong Kong – In Memory Of Harinder Veriah

04/03/01 – A speech by Martin Jacques

-

Anti-racists take on Hong Kong’s secret shame

-

Racism “Threat to our international image”

05/03/01 – South China Morning Post

-

Inquest casts doubt on hospital care

-

A Season in Paradise

30/11/02 – The Guardian

-

BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Interview

-

Race-row widower sues over wife’s death

18/01/03 – South China Morning Post

-

To one widower, anti-racism law is a memorial to tragedy

10/07/03 – South China Morning Post

-

My wife didn’t die in vain

-

The Global Hierarchy of Race

-

Press Release: Statement from Martin Jacques

31/03/10

-

It seemed impossible, but at last Martin Jacques got justice for the wife he loved

04/04/10 – The Observer

Thank You...

“I like HVT because it is the best. We get free meals. I like going for tuition. The teachers are very nice and they want me to become a good student.”

Nur Syahirah Dayana Bt Abdul Rahman Std 4